Deep Learning and Computer Vision in R: A Practical Introduction (1.1)

BIBC2025 workshop - Introduction

Patrick Li

RSFAS, ANU

About me

I am Patrick Li.

Education Background I hold a PhD in Statistics. My research focused on computer vision and data visualization, with an emphasis on developing visual analytics methods to assess residual plots.

Current Work I am currently working at ANU, primarily on machine learning, image analytics, and plant phenotyping projects.

Past Experience in Computer Vision My PhD research involved applying computer vision techniques to evaluate residual plots. I have worked on a food safety project where I helped collect human-subject data, trained vision language models to answer food safety–related questions, and trained object detection models for food safety area detection. I also contributed to a project analysing sperm–egg cell videos and images to understand factors related to successful IVF outcomes.

Content summary

- > Overview of computer vision (CV)

reticulatebasics- Image classification

- Hyperparameter tuning

- CV model interpretation

- Object detection

- Image segmentation

Disclaimer

Code and theory

This workshop is a hands-on introduction to modern computer vision in R. You’ll work through code examples and practical exercises. Theory will be covered only to the extent needed to understand the key ideas and statistical foundations behind the models.

Reproducibility

Computer vision models can be only partly reproducible due to parallel computation. Don’t be surprised if your results differ from those shown in the materials.

Hardware and time limit

Training time-consuming models will not be required during the workshop, as participants may have different hardware setups. Example training codes are provided in the materials, and exercises will focus on exploring pre-trained models.

Expectation

How confident should I be coming into this workshop?

If you have a background in statistics, you are good to go!

There will be some new concepts and terminology, but almost everything can be understood using your statistical intuition.

Don’t be intimidated by CV jargon!

Overview of computer vision

Computer vision

Computer vision is a broad field concerned with enabling machines to interpret and understand visual information from the world.

- Image classification: Assign label(s) to an entire image

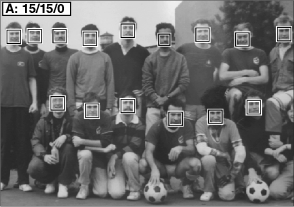

- Object detection: Locate and classify multiple objects within an image using bounding boxes

- Image segmentation: Label each pixel with a class, producing a detailed mask of objects

- Image generation: Create realistic or artistic images from scratch or from a condition

- Visual Question Answering: Answer questions about an image by understanding its content

- …

Early CV research (before 1980s)

Early CV research relied heavily on geometric reasoning, algebraic formulations, and handcrafted rules.

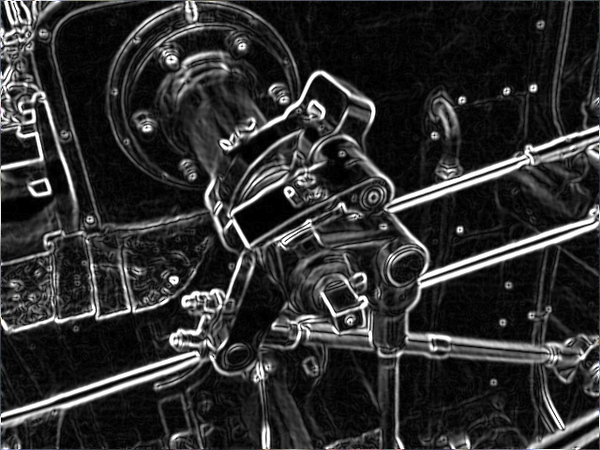

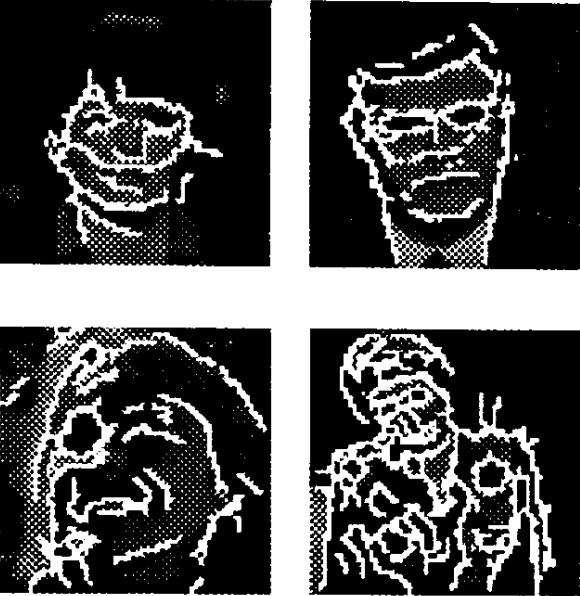

Edge and line detection, Sobel operator (1968)

Digit recognition, N-tuple method (1959)

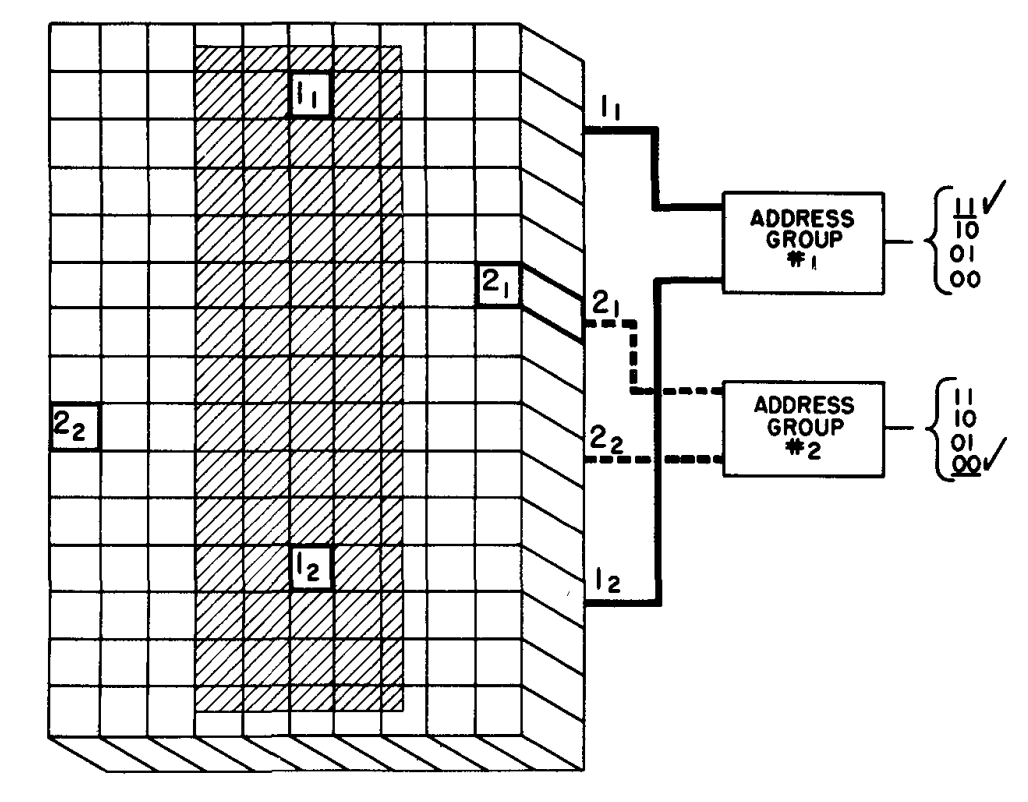

Image segmentation, recursive region splitting (1978)

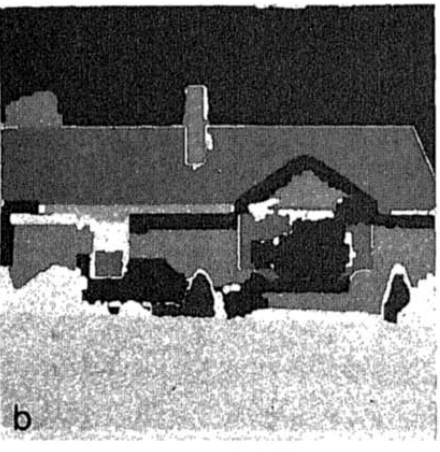

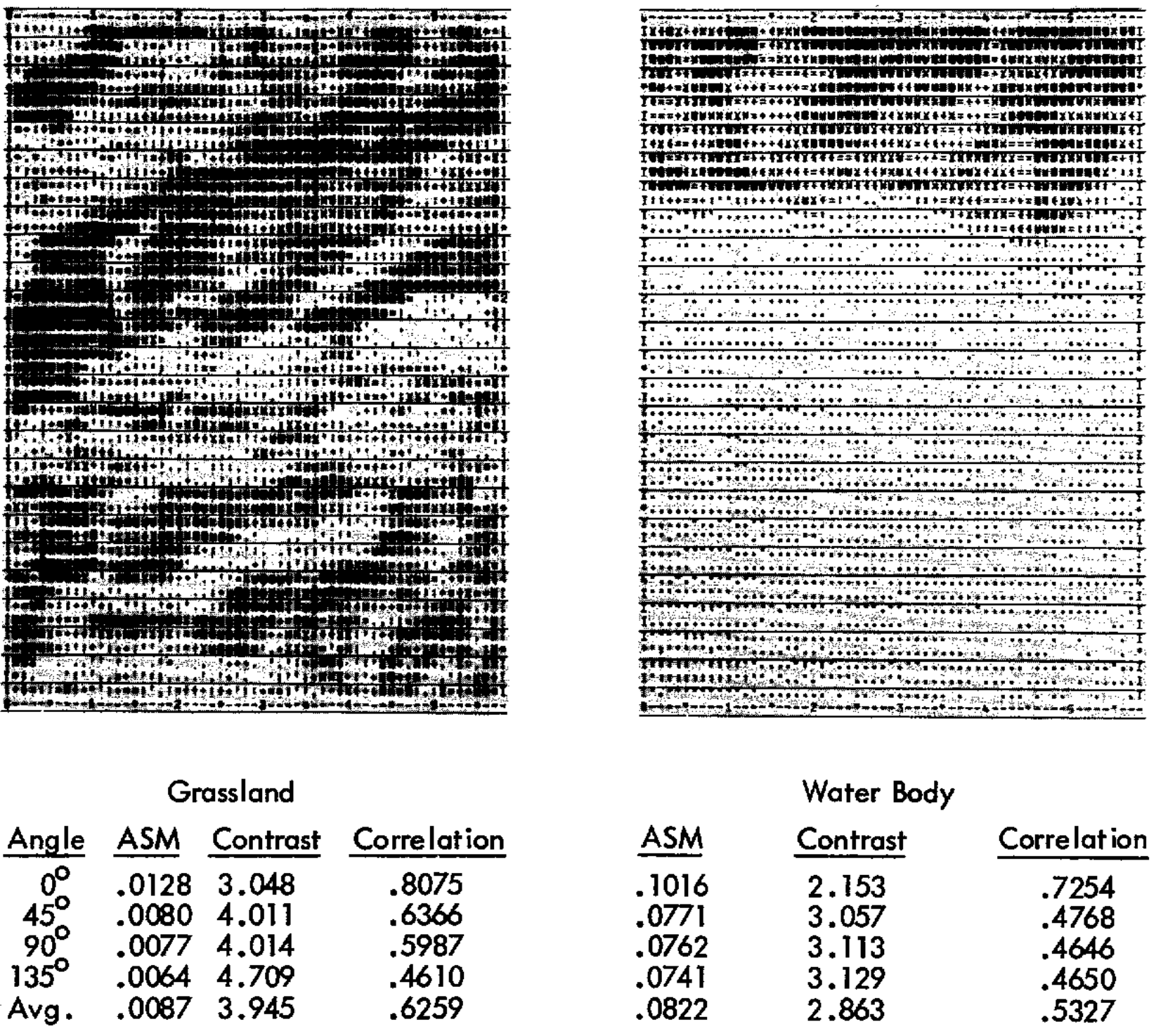

Image classification, texture analysis (1973)

Rise of CNN (1980s - 1990s)

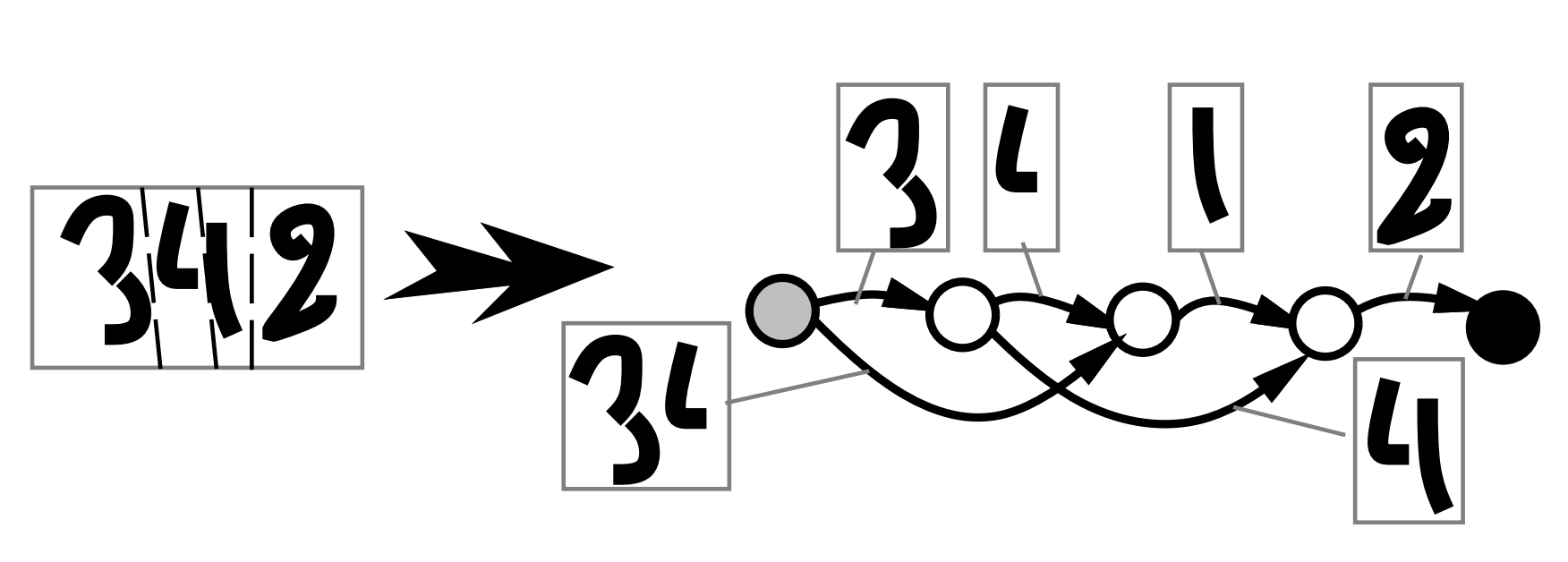

The first convolutional neural network (CNN) Neocognitron was introduced in 1980, but it was LeCun’s LeNet for digit recognition (late 1980s – 1990s) popularised it.

Document recognition, LeNet-5 (1998)

Face detection (1998)

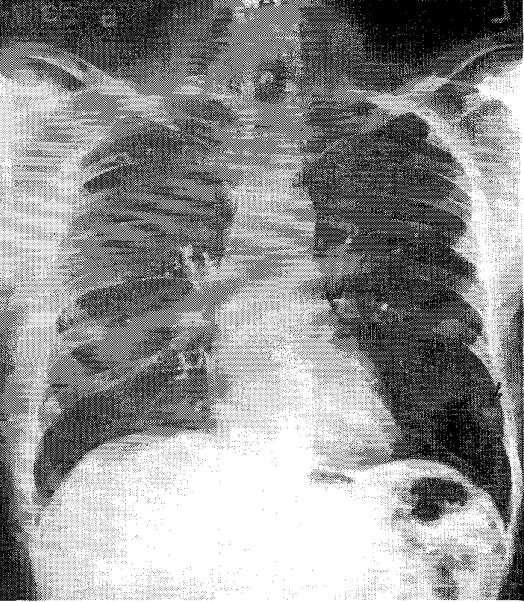

Lung nodule detection (1995)

Image segmentation, Cresceptron (1992)

Feature descriptors era (2000s)

During the 2000s, due to hardware limitations, research largely shifted toward hand-crafted feature descriptors and training classifiers such as SVMs on top of them.

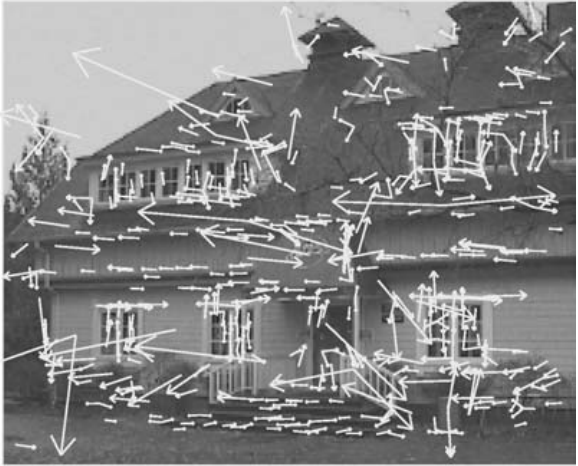

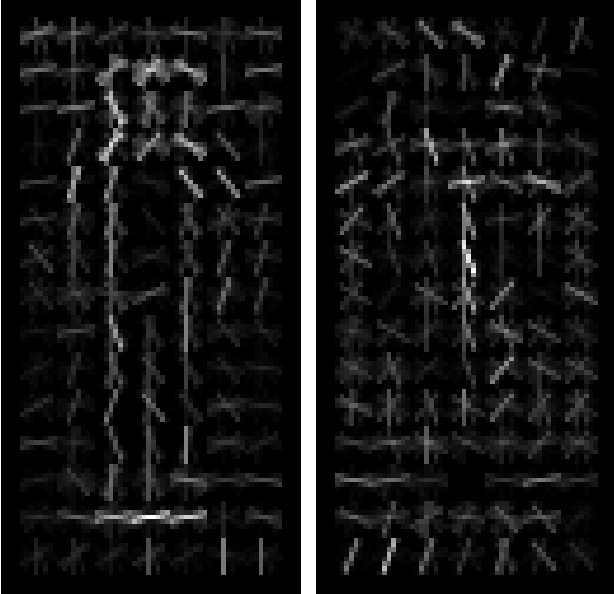

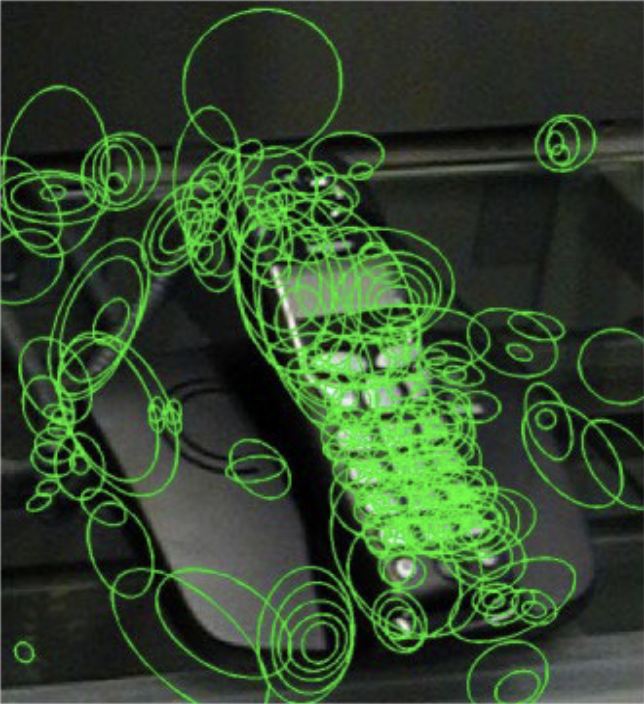

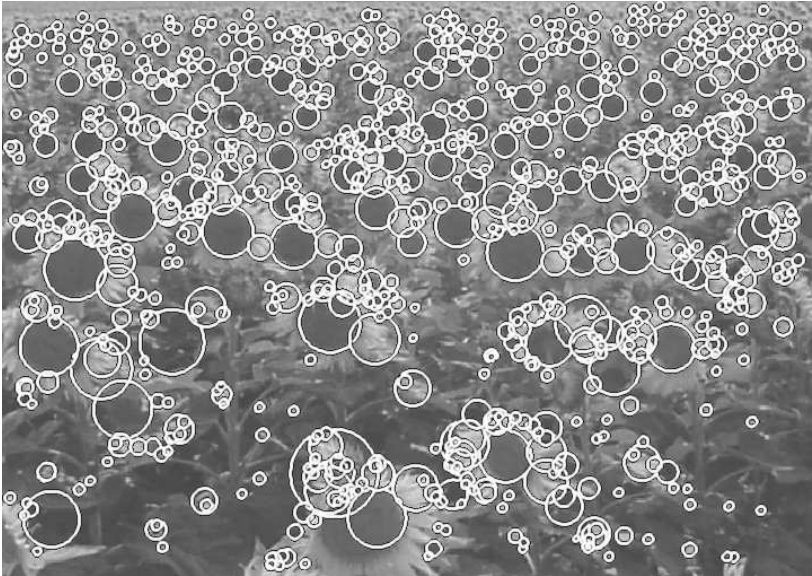

Scale Invariant Feature Transform (2004)

Histograms of Oriented Gradients (2005)

Bag of visual words (2004)

Speeded up robust features (2006)

CNN deep learning era (2010s)

Powerful GPUs and the introduction of the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) sparked the rapid advancement of modern computer vision models.

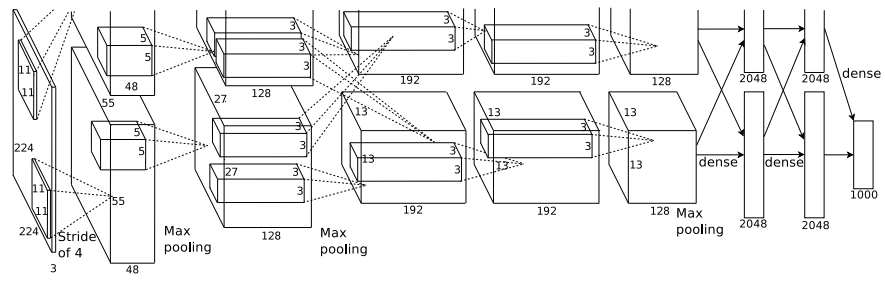

Image classification, AlexNet (2012)

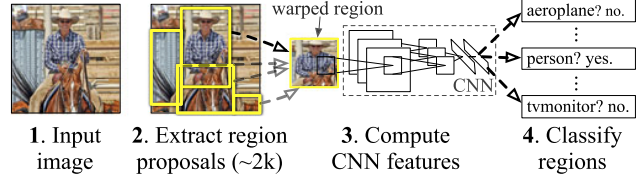

Object detection, R-CNN (2015)

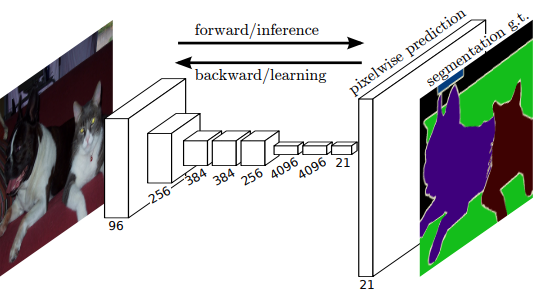

Image segmentation, Fully Convolutional Network (2015)

Image generation, Generative Adversarial Nets (2014)

Transformer era (2020s)

The 2020s are defined by transformer-based architectures, emphasising global context, scalability, and multi-modal learning.

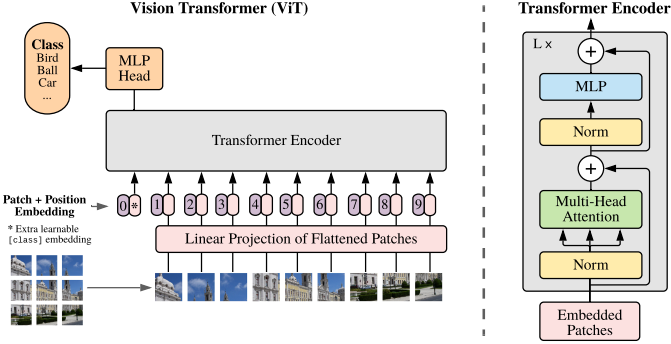

Image classification, Vision Transformer (2020)

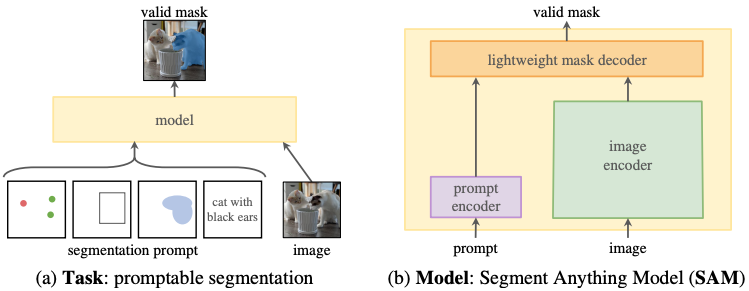

Image segmentation, Segment Anything Model (2023)

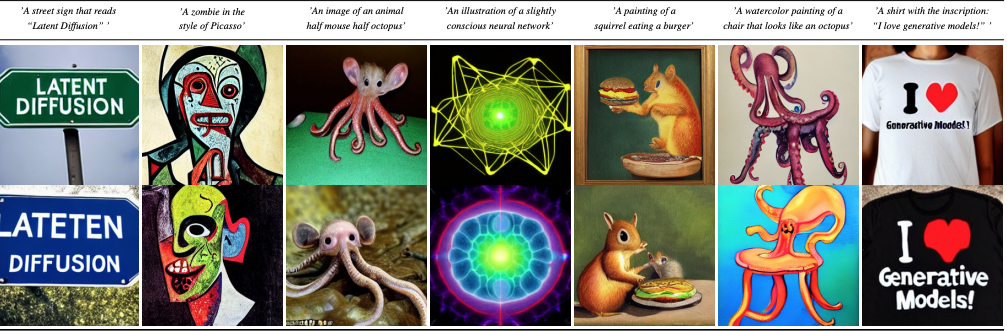

Text-to-Image generation, Latent Diffusion Model (2022)

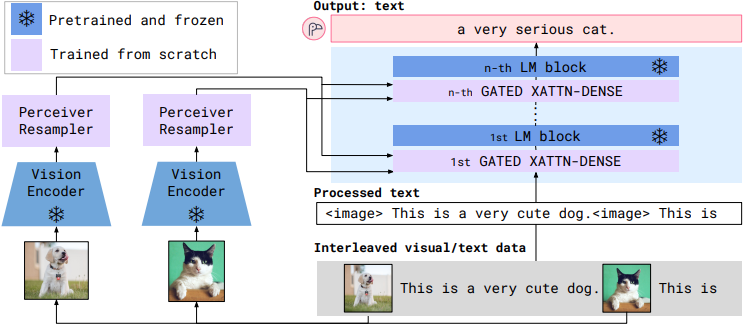

Vision question answering, Visual Language Model (2022)

What’s next? (2030s)

We don’t know if a breakthrough on the scale of CNNs or Transformers will occur.

Nor is it clear whether traditional statistical knowledge will remain relevant to future computer vision research.

By reading the literature from the 1950s to today, you fill find less and less traditional statistics involved.

Research is relying more on higher-level conceptual thinking.

Overview of CV tools and platforms

Traditional CV tools and platforms

Back in the day, computer vision tools were not packaged software like today but rather collections of custom routines written mainly in assembly, C, or Fortran.

Image processing libraries began to emerge in 1980s, such as:

- Khoros (late 1980s)

- MATLAB Image Processing Toolbox (early 1990s)

- Intel Image Processing Library (IPL) (mid 1990s)

- ImageJ (late 1990s)

- OpenCV (2000)

- scikit-image (2009)

Deep learning frameworks

With CNNs gaining popularity, new open-source deep learning frameworks appeared in the 2010s.

These frameworks all shares common characteristics:

- Tensor-based computation

- core data structures are multi-dimensional arrays (tensors)

- GPU acceleration

- computation can be offloaded to GPUs for parallel processing

- Automatic differentiation

- Gradient of loss with respect to parameters are computed automatically

- Basic neural network building blocks

- Common layers, activations, losses, and optimisers are provided

![]() Theano (2010 - 2017)

Theano (2010 - 2017)

Theano was released by the MILA Lab, Montréal around 2010.

- Widely used in the early 2010s for neural network research

- Forks:

- Theano-PyMC: Maintained for probabilistic programming

- PyTensor: Actively maintained, modernised successor with GPU and symbolic support

![]() Caffe (2013 - 2018)

Caffe (2013 - 2018)

Caffe was released by UC Berkeley in December 2013 by Yangqing Jia.

- Dominated computer vision research and industry applications (2013 - 2016)

- Forks:

- Caffe2: Facebook’s production-focused successor (2017)

- OpenCaffe: Community maintenance efforts

- Merged into PyTorch ecosystem (2018)

![]() CNTK (2015 - 2019)

CNTK (2015 - 2019)

CNTK (Microsoft Cognitive Toolkit) was released by Microsoft Research in 2015.

- Strong performance in speech recognition and reinforcement learning

- Legacy:

- Archived: Code available but no active development

- ONNX: Microsoft’s contributions live on in the Open Neural Network Exchange format

- Users migrated primarily to PyTorch and TensorFlow

![]() TensorFlow (2015 - present)

TensorFlow (2015 - present)

TensorFlow was released by Google Brain in November 2015.

- Dominated industry and research (2016 - present), stable v1.0.0 in 2017

- Current Status:

- TensorFlow 2.x: Actively maintained with Keras as official high-level API

- TensorFlow Lite: Mobile and embedded deployment

- TensorFlow.js: Browser-based machine learning

![]() Keras (2015 - present)

Keras (2015 - present)

Keras was released by François Chollet in March 2015.

- High-level, user-friendly API designed to run on top of TensorFlow, Theano, or CNTK with a focus on fast experimentation

- Became the most popular high-level neural networks API (2015 - 2019)

- Current Status:

- tf.keras: Integrated into TensorFlow 2.0 as default API

- Keras 3.0 (2023): Multi-backend support (TensorFlow, JAX, PyTorch)

- Actively maintained by Google and the community

![]() PyTorch (2017 - present)

PyTorch (2017 - present)

PyTorch was released by Facebook AI Research (FAIR) in January 2017.

- Rapidly gained popularity in research community, absorbed Caffe2 (2018)

- PyTorch Foundation: Established under Linux Foundation (September 2022)

- Current Status:

- Dominates research: ~95% market share with TensorFlow

- torchvision, torchaudio, torchtext: Rich ecosystem of domain libraries

![]() JAX (2018 - present)

JAX (2018 - present)

JAX was released by Google Research in December 2018.

- Not a traditional DL framework — a numerical computing library with autodiff

- Growing adoption in research, especially at Google Brain and DeepMind

- Current Status:

- Actively maintained by Google Research

- Focus: Advanced research, scientific computing, and custom architectures

Choice for this Workshop

We will use PyTorch as the backend and Keras as the high-level API.

Keras was originally tied to TensorFlow, but TensorFlow development has slowed, and internal interest at Google seems to have decreased, similar to other past Google products.

Keras 3.0 now supports multiple backends, so the same code can run on TensorFlow, PyTorch, or JAX.

Today, PyTorch is the main choice for research and fast experimentation, and most new models are built with it.

It matters less which framework you start with. Most share similar core designs, so once you understand the fundamentals, your experience is easily transferable.

Slides URL: https://ibsar-cv-workshop.patrickli.org/ | Canberra time

Theano (2010 - 2017)

Theano (2010 - 2017) Caffe (2013 - 2018)

Caffe (2013 - 2018) CNTK (2015 - 2019)

CNTK (2015 - 2019) TensorFlow (2015 - present)

TensorFlow (2015 - present) Keras (2015 - present)

Keras (2015 - present) PyTorch (2017 - present)

PyTorch (2017 - present) JAX (2018 - present)

JAX (2018 - present)